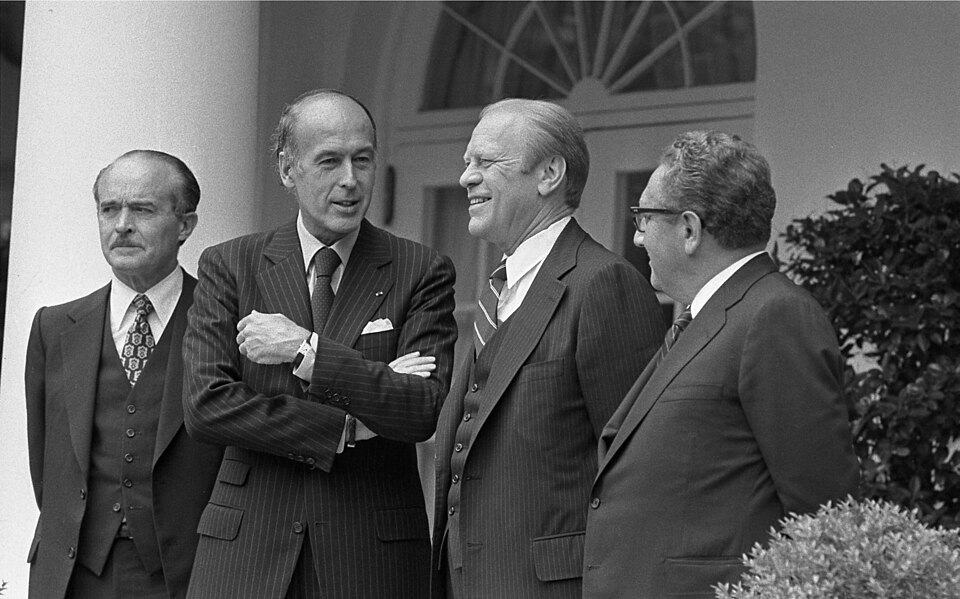

(© People's Liberation Army)

Le développement des forces de missiles chinoises soulève des questions sur l'équilibre des puissances en Asie et au-delà. Les avancées technologiques de la People's Liberation Army Rocket Force (PLARF), comme les tests de missiles DF-31AG, renforcent la dissuasion nucléaire chinoise, mais augmentent aussi les tensions régionales. Les enjeux incluent la course aux armements, la stabilité géopolitique et le risque de prolifération nucléaire, exigeant une réponse stratégique coordonnée de la communauté internationale.

People’s Liberation Army Rocket Force and its Missile Forces

The development of China's missile forces raises questions about the balance of power in Asia and beyond. Technological advances by the People's Liberation Army Rocket Force (PLARF), such as the DF-31AG missile tests, strengthen China's nuclear deterrent but also increase regional tensions. Issues include the arms race, geopolitical stability, and the risk of nuclear proliferation, requiring a coordinated strategic response from the international community.

China’s missile forces have been discussed by policy makers and strategic analysts in the recent decades owing to Beijing’s institutional and technological amendments that played major factors in the missile development program. One important arm of Chinese military is the People Liberation Army Rocket Force (PLARF) and its missile capabilities. Thus it becomes relevant in the present circumstances to discuss PLARF and its missile capabilities.

China’s dream and PLARF

China’s missile forces have undergone technological advancements owing to the President Xi Jinping’s Chinese Dream that includes the Great Rejuvenation of the Chinese nation (1). Missiles are viewed as key component of Chinese military strategy. There are also speculations that China spends more on defence as defence budget than it announces.

In September 2024, Beijing tested-fired into the South Pacific an intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM), the Dong Feng-31 AG (DF-31AG), an advanced version of the DF-31A (2). The missile was believed to have been fired from the Hainan Island, an unusual location for ICBM missile. For the first time, China reached a target of 11,700 kms away into the Pacific. What was surprising was that there was no permanent ICBM brigade deployed in the Hainan province (3). This test highlighted two important aspects.

Il reste 93 % de l'article à lire

.jpg)

_astronaut_Sophie_Adenot_(jsc2025e058846_alt).jpg)